Mesa Verde National Park, located in the Southwest corner of blue state Colorado, plays a unique role in outdoor tourism. Established in 1906, this park is charged with protecting the vestiges of an ancestral Native American culture — the Anasazi. Indeed, it remains the only national park dedicated solely to the preservation of ancient man-made works.

Mesa Verde National Park, located in the Southwest corner of blue state Colorado, plays a unique role in outdoor tourism. Established in 1906, this park is charged with protecting the vestiges of an ancestral Native American culture — the Anasazi. Indeed, it remains the only national park dedicated solely to the preservation of ancient man-made works.

The name Anasazi comes from a Navajo word meaning “ancient ones.” Archaeologists believe this prehistoric culture inhabited Mesa Verde from around 550 A.D., if not earlier, to the late 1270s. Then, quite mysteriously, the Anasazi began migrating south into present-day New Mexico and Arizona. By 1300, Mesa Verde was deserted.

Despite decades of excavation, research, and analysis, knowledge of the Anasazi is still subjective. They possessed no written language; they recorded their thoughts by a few symbols painted on earthenware jars or by petroglyphs carved on canyon walls and in cliff dwellings. But their ruins speak volumes of a culture adept at building, farming, and artistry. And as a testament, the park contains the most complete existing records of the Anasazi people.

The initial reports of ruins at Mesa Verde surfaced in 1874. Then, in 1888 came the discoveries of Cliff Palace and Spruce Tree House by local ranchers Richard Wetherill and Charles Mason. Their findings prompted an increase in visits to the ruins. Historians point out that while the Wetherill family kept records of their amateur excavations, others ravaged the sites and stole artifacts. This sacking spurred enough protests to effect the founding of the national park as a safeguard for the ruins.

As a timeline, the cliff dwellings represent only the final remnant of the Anasazi culture. The park’s Chapin Mesa Museum presents a broader picture, including displays of exceptional basketry and weaving. These are the hallmarks of the earlier Anasazi ancestors.

Author’s Note:

Many current historical accounts of Mesa Verde use the term “Ancestral Pueblo” or “Classic Pueblo” instead of Anasazi. In most cases, the terms are interchangeable, depending on the historical reference. This Blue State Travel article uses the more traditional term Anasazi throughout most of its content.

Mesa Verde Vantage Points

Mesa Verde Vantage Points

The Mesa Verde National Park entrance is 10 miles east of Cortez on U.S. Highway 160 or eight miles west of Mancos. As you continue inside the park about 15 miles to the Far View Visitor Center, you’ll see numerous beautiful canyons and plateaus. The overlooks provide views of the valleys below, including the towns of Cortez and Mancos. Mesa Verde itself is one of the largest mesas in the Southwest, standing on the right bank of the Mancos River. The cliff dwellings are situated in the walls of small rough canyons that slope down from the mesa top toward the river.

Aside from the major ruin attractions, you can see other cliff dwellings from canyon-rim vantage points via self-guiding excursions on Ruins Road. Wayside exhibits interpret the development of Anasazi culture from the Basketmakers through the Classic period. These roads are open from 8:00 a.m. until sunset. During winter, the mesa-top loops are open as weather permits. When snow conditions allow, visitors may snowshoe or cross-country ski on roadways. Always check at the information centers for park and road conditions. All cliff dwellings are closed and cannot be entered during winter.

The route to Wetherill Mesa offers some of the best sightseeing and camera viewpoints in the park. On a clear day, you can view landmarks in all four states. These include Shiprock in New Mexico, Monument Valley in Arizona and Utah, Colorado’s Sleeping Ute Mountain to the west, and the rugged San Juan Mountains to the north and east. At Wetherill Mesa, you can explore cliff dwellings and mesa-top ruins. Be sure to allow at least a full day for your visit. Wetherill Mesa is closed during the winter months.

Anasazi Artistry and Culture

Although mesa-top ruins and cliff dwellings are the major draw to Mesa Verde, there are cultural features, too. At one point, more than 40,000 Anasazi lived in Montezuma Valley. Their human remains and traces of mesa-top crops of corn, beans, and squash have been found among the ruins. The early Anasazi were known as Basketmakers because of their impressive skill at that craft. But they also left archaeological clues to their daily and religious life in the form of tiny artifacts. Over generations, they honed an aesthetic sense in the objects they created. And their influence of design and fine craftsmanship persists today in modern Pueblo cultures.

Examples include deer-bone scrapers, five inches long and handsomely inlaid with turquoise and jet, showing superior quality; ceremonial objects, such as stylized 25-inch wooden altar effigies resemble images still used in Native American religion today. Pottery, the Anasazi’s chief artistic legacy — usually made by the women — varied regionally in style. Also, their pottery designs evolved through generations. Black-and-white drawings on a white background replaced crude designs on a dull gray. Later, this imagery was complemented with more colorful renderings.

By the time the Anasazi reached their Classic period, round towers and complex kivas were replacing some of their more traditional square designs. And along with this rising level of craftsmanship in masonry work came more advanced forms of pottery, weaving, jewelry, and even tool-making.

Mesa-Top Attractions

For about 600 years, the Anasazi culture primarily inhabited the fertile tops of Mesa Verde. They dry farmed the terrain and hunted animals native to the region. Remnants of these mesa-top sites exist today, including Badger House Community, Cedar Tree Tower, Far View and Sun Temple. Throughout the park, you can engage in free self-guided tours on Wetherill Mesa, Chapin Mesa, and the Mesa Top Loop Road. Here’s a brief park description of what you’ll experience:

• Badger House Community comprises four sites along a paved and graveled walking/bicycling trail. These include a Modified Basketmaker pit-house, developmental Anasazi (Ancestral Puebloan) village, Badger House, and Two Raven House. The trail starts near the Wetherill Mesa kiosk, a 12-mile, 45-minute drive along Wetherill Mesa Road. The 2.25 mile round-trip hike is marked with signs explaining each site.

• Cedar Tree Tower is close to the four-way intersection on Chapin Mesa. It is one of several tower sites that exist on the mesa tops, built during the Classic period (1100 to 1300). Adjacent to Cedar Tree is the Farming Terrace Trail, a one-half-mile looping path. The short hike shows prime examples of Anasazi check dams and farming terraces used more than 800 years ago.

• Far View, located near Chapin Mesa, was once densely populated. Nearly 50 villages have been identified within a half-square-mile area. Park visitors can view several stabilized sites linked by a short hiking trail. They include Far View House, Pipe Shrine House, Coyote Village, Far View Reservoir, Megalithic House, and Far View Tower.

• Sun Temple, which modern Pueblo historians regard as a ceremonial structure, is on Mesa Top Loop Road. The formation’s primary features are its fine masonry walls — double-coursed and filled with a rubble core. Some contend that the symmetrically planned D-shaped building was never fully completed.

Mesa Verde’s Cliff Dwelling Evolution

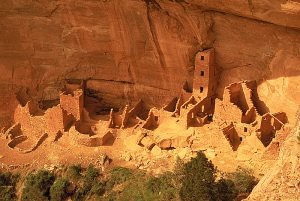

The vast area of Mesa Verde measures 15 miles long, 18 miles wide, and rises 2,000 feet above a surrounding plateau. Resting on this mesa are Anasazi ruins comprising nearly 5,000 archaeological sites spread across 40 miles of road. These include early pit houses, multistoried cliff pueblos, farms, ceremonial shrines or kivas, towers, and petroglyphs.

Most researchers agree that the Anasazi vacated their mesa tops around 1200 to build elaborate pueblos in the overhanging cliffs below. Even then, not all relocated to the cliff alcoves; many remained at their mesa-top communities. Some continued farming while residing below in the alcoves, repairing, remodeling, and building new dwellings. Still, there was a major population shift among the Anasazi, although the reason why is not certain. Speculation ranges from enemy defense or better protection from climate extremes to religious or cultural pursuits.

A bulk of the cliff dwellings were constructed in the middle decades of the 13th century, according to historians. The structures vary from one-room houses to villages containing more than 200 rooms. The rooms average about 6 feet by 8 feet, large enough for two or three persons. Isolated rooms in the backs of houses and on the upper levels were generally used for storing crops. Interestingly, it appears that all architectural styles were random. In other words, no standard blueprint exists. The Anasazi custom-fitted their designs to the available space.

As you examine their ancient work, most room walls are single layers or courses of rectangular sandstone blocks. The mortar used between the sandstone layers was a mixture of soil, water, and ash. The masonry skills vary in quality; you can actually see rudimentary construction alongside more skillfully crafted wall structures. Many rooms have remnants of plaster on the inside walls, once decorated with painted designs.

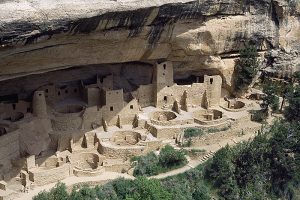

Cliff Palace

Several of Mesa Verde’s major cliff dwellings can only be visited through a ranger-guided tour (fee required), beginning with Cliff Palace on Chapin Mesa. Others include Balcony House and Long House. Before driving to any of these guided tour sites, be sure to purchase tickets at the Mesa Verde Visitor and Research Center. Open from 8:00 a.m. to sunset, the Cliff Palace Loop Road provides access to Cliff Palace, Balcony House, and additional overlooks. The latter includes Square Tower House, Navajo Canyon View, Sun Point View, Soda Canyon Overlook, and Pueblo Village.

Some studies claim that Cliff Palace, the largest of the cliff dwellings, contain as many as 200 rooms, along with more than 20 kivas. To put that size or number in perspective, here’s an interesting fact. Of the nearly 600 cliff dwellings located within the park’s boundaries, the majority have five rooms or less each; many are just single-room structures. With an estimated population of 100, Cliff Palace was probably a social, administrative site with high ceremonial usage.

Sandstone, mortar, and wooden beams comprise the basic construction materials for Cliff Palace and the other cliff dwellings. The Anasazi shaped the sandstone blocks using harder stones collected from nearby river beds. Also, within the mortar are tiny pieces of stone called “chinking.” Chinking stones filled gaps within the mortar, adding structural stability. And the Anasazi decorated many of the wall surfaces with earthen plasters of pink, brown, red, yellow, or white.

Long House

Long House

Mesa Verde’s second largest cliff dwelling, Long House, is located on Wetherill Mesa in the western section of the park. You can access this site via a winding road that leaves the main park road just beyond the Far View Lodge (mile marker 15). The steep route follows a historic fire trail for 12 miles, which features a series of turnouts and overlooks. Allow at least two hours for the ranger-guided tour.

Long House, which showcases around 150 rooms, was excavated between 1959 and 1961 as part of the Wetherill Mesa Archeological Project. This initiative was funded by the National Park Service and the National Geographic Society. Overall, the project facilitated the excavation of 15 sites on Wetherill Mesa between 1958 and 1963.

Park officials emphasize that Wetherill Mesa offers a more relaxed Mesa Verde experience, one designed for outdoor enthusiasts. Aside from the Long House tour, you can hike or bicycle the five-mile Long House Loop. This paved route leads to various trailheads such as Badger House Community, Kodak House Overlook, Long House Overlook, and the Nordenskiold Site #16 trails.

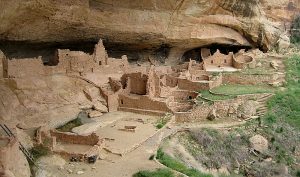

Spruce Tree House

Spruce Tree House, situated near the Chapin Mesa Archeological Museum, is the third largest Anasazi cliff dwelling in Mesa Verde. Constructed between 1211 and 1278, the structure contains about 130 rooms and eight kivas or ceremonial chambers. It sits within a natural alcove measuring 216 feet at its greatest width and 89 feet at its greatest depth. Its estimated population was 60 to 80 inhabitants.

The cliff dwelling was first discovered in 1888 by two local ranchers searching for stray cattle. They saw a large Douglas spruce (later called Douglas fir) growing from the front of the dwelling to the mesa top. As the story goes, the ranchers first entered the dwelling by climbing down this tree — later cut down by another early explorer. Following excavation in 1908, Spruce Tree House opened for public visitation.

Jesse Fewkes of the Smithsonian Institution headed the excavation project. He removed debris from fallen walls and roofs and stabilized the remaining walls. Due to the protection of the overhanging cliff, Spruce Tree House deteriorated very little through the years, requiring little supportive maintenance. Unfortunately, due to the more recent and continued safety concerns relating to rock falls, the site remains closed for the foreseeable future. However, overlooks near the museum still offer excellent views of the cliff dwelling.

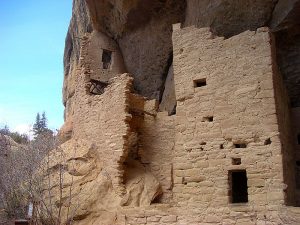

Balcony House

This well-preserved Anasazi ruin rests on Chapin Mesa along the Cliff Palace/Balcony House Road. With its 40 rooms, kivas, and plazas, the structure is a medium-size cliff dwelling by comparative standards in Mesa Verde. However, the special distinction of Balcony House is its evolution of room construction over time. The visible evidence lies in the tunnel, passageways, and modern 32-foot entrance ladder that are characteristic of this structure. In fact, park guides tout the Balcony House tour as one of the most adventuresome in the park.

Historical records cite a group of prospectors, led by S. E. Osborn, as first entering Balcony House in the spring of 1884. Accompanied by W. H. Hayes and George W. Jones, the goal of their mission was to locate coal seams in nearby Mancos Canyon. Both Osborn and Hayes left their names in the site; later that spring, Hayes left his name across the canyon in Hemenway House. In later writings, Osborn describes some of the other sites he visited in the Mesa Verde region from 1883 through 1884.

Park historians are also proud to note that adventurer Jesse Nusbaum excavated Balcony House in 1910. Nusbaum was not only a renowned archeologist, he was also one of the first superintendents of Mesa Verde National Park.

Step House

Step House is one of several sites on Wetherill Mesa, open seasonally (mid-May to mid-October) on a self-guided basis, with no fee required. Historians say this Anasazi ruin is unique because of its clear indication of two separate occupations of the same site. One occupation is from the Modified Basketmaker culture dating back to 626 A.D. Their remnants are between the old stone steps on the south and the large boulders on the north. The rest of the alcove houses a masonry pueblo dating back to 1226, the Classic Pueblo times.

A one-mile steep trail takes you to this cliff dwelling. Because this is a self-guided excursion, you can enter and exit at your convenience. A park ranger is on-site in the dwelling to answer any questions. The trailhead to Step House is near the Wetherill Mesa information kiosk, a 12-mile drive along the Wetherill Mesa Road. As with Cliff Palace, the winding road leaves the main park road just beyond the Far View Lodge (mile marker 15). You should allow at least 45 minutes to visit Step House.

All the sites on Wetherill Mesa provide for a much quieter and slower-paced visit. Park guides suggest it is worthwhile to spend at least half-day on Wetherill Mesa. Generally, it takes three to four hours to visit the Wetherill sites, but trail hiking or bicycling in the area can easily take longer.

Blue State Travel expresses appreciation to the National Park Service for providing detailed information regarding the cliff dwelling sites within Mesa Verde.

Other Mesa Verde Attractions

A five-mile drive from the Mesa Verde National Park entrance brings you to Morefield Campground, open from April to October. This facility has more than 500 campsites, with a full complement of services — showers, laundry, groceries, carryout food, firewood, and fuel. Campsites for the physically impaired are available, too. Some utility hookups are available, and there is a dump station for recreational vehicles. Additionally, near the park entrance are several commercial campgrounds.

Three hiking trails originate in the Morefield area: Point Lookout Trail (2.2 miles), Knife Edge Trail (2 miles), and Prater Ridge Trail (7.8 miles). Just a few miles east from the campground is Mancos Valley Overlook; to the west is Montezuma Valley Overlook. Further west, about six miles on Wetherill Mesa Road, is Park Point Overlook (8,572 feet). This is the highest park elevation for vehicles, where you can see mountain ranges 200 miles away. To its renown, Park Point offers superb views of the entire Four Corners region. Another five miles west is Geologic Overlook. Wetherill Mesa Road is open May through September, weather permitting. Maximum vehicle weight allowed is four tons; maximum vehicle length allowed is 25 feet. You cannot bicycle, either.

Additionally, there other trailheads for hiking enthusiasts located to the south on Chapin Mesa. These include Farming Terrace Trail (one-half mile), Soda Canyon Overlook Trail (1.5 miles), Spruce Canyon Trail (2.4 miles), and Petroglyph Point Trail (2.4 miles). At Petroglyph Point, a 12-foot-wide panel of rock exhibits one of the largest inscriptions made by the Anasazi. To the far west, on Wetherill Mesa Road, you’ll discover several more viewpoints — Rock Canyon Tower, McElmo Canyon, Fire Recovery, and Window to the Past.

Park Entrance Fees

Mesa Verde National Park’s entrance fees vary on a calendar basis. During peak visitor season, May through October, the fee is $25 for private vehicles. From January through April and November through December, the fee is $15 per vehicle. For motorcycles, the fee is $20 May through October; January through April and November through December, the fee is $10. For a bicyclist or an individual on a noncommercial bus, the fee is $12 May through October; January through April and November through December, the fee is $7. All entrance fees are valid throughout the park for seven days.

Annual park passes are available, too, $50 per person, beginning from the date of purchase. America the Beautiful (ATB) series passes are also available, with varying prices for military service members, seniors, and special access individuals. Accepted forms of payment include cash, travelers’ checks, standard credit cards (Mastercard, VISA, Discover, American Express, or Diners Club). If you use personal or commercial checks, you’ll need additional identification.

Park entrance fees for individuals on noncommercial tours (organized groups) vary depending on vehicle capacity and the seasonal calendar. Holders of ATB passes, Golden Passports, Annual Mesa Verde passes, and those under 16 years of age are exempt from payment of fees. The total fee charged for any organized noncommercial group will not exceed the charge for a commercial tour fee. Generally, the fees range from $7 to $12 per person for vehicles with a capacity of 16 or more individuals. For groups less than 16 individuals, the fee ranges from $15 to $25 per vehicle. The noncommercial group fee is good for seven days from the date of purchase.

Some Final Advice to Mesa Verde Visitors

Visiting a cliff dwelling can be strenuous. Elevations in Mesa Verde National Park can vary from 6,000 to 8,500 feet. Please consider your physical health before hiking or going on tours; hiking or touring cliff dwellings is not recommended for persons with heart or respiratory conditions. Trails are steep and uneven, with steps and ladders often necessary for climbing. As a healthy alternative, you can view most of the major cliff dwellings from overlooks. Hikers must register at the ranger’s office before attempting the longer park trails at Petroglyph Point and in Spruce Canyon.

Although you can bicycle on all park roads except those on Wetherill Mesa, there are no designated bicycle lanes. Park roads and trails may be hazardous in winter, so be sure to stop at the entrance gate for current information on road conditions and tour schedules. Also, do not drive or park trailers and towed vehicles beyond Morefield Campground; they must remain at the entrance parking area or at the Morefield Village parking area.

Children require supervision at all times, especially on trails, at the cliff dwellings, and near canyon rims. Although there are no height or age restrictions for tours, children must be capable of walking the extent of the trails, climbing ladders, and negotiating steps independently. Please carry all infants in backpacks while on tours; adults carrying children must be able to maintain mobility and balance.

Finally, professional thieves sometimes target visitors, robbing campsites and locked vehicles. Take valuables with you or leave them in a secure place; locked cars (and trunks) are not always the answer. Report all thefts immediately to the nearest ranger station.

For further information regarding ancient archaeological sites and other scenic destinations in the Southwest, visit here.